Complex Numbers

A nonempty bounded subset of ZZ contains a maximal

element

This assertion is used several times in these notes, here is its proof.

Let m be an arbitrary element of the set M in question, there is at least one,

by assumption.

Further, let c be the bound. Then the algorithm

for n=c:-1:m do: if n ∈ M, break, fi, od

is guaranteed to halt after finitely many steps, and the current value of n is the

maximal element

of M.

Also, note the corollary that a bounded function into the integers takes on its

maximal value:

its range then contains a maximal element and any preimage of that maximal

element will do.

Complex numbers

A complex number is of the form

z = a + ib.

with a and b real numbers, called, respectively, the real part of z and

the imaginary part of z,

and i the imaginary unit, i.e.,

Actually, there are two complex numbers whose square is −1. We denote the other

one by −i. Be

aware that, in parts of Engineering, the symbol j is used instead of i.

MATLAB works internally with (double precision) complex numbers. Both variables

i

and j in MATLAB are initialized to the value i.

One adds complex numbers by adding separately their real and imaginary parts.

One multiplies

two complex numbers by multiplying out and rearranging, mindful of the fact that

i2 = −1. Thus,

(a + ib)(c + id) = ac + aid + bic − bd = (ac − bd) + i(ad + bc).

Note that both addition and multiplication of complex numbers is commutative.

Further, the

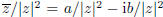

product of z = a + ib with its complex conjugate

is the nonnegative number

and its (nonnegative) squareroot is called the absolute value or modulus of z

and denoted by

For z ≠ 0, we have l z l ≠ 0, hence

is a well-defined complex number. It

is a well-defined complex number. It

is the reciprocal of z since

,

of use for division by z. Note that, for any two complex

,

of use for division by z. Note that, for any two complex

numbers z and

,

,

It is very useful to visualize complex numbers as points in the so called

complex plane, i.e.,

to identify the complex number a + ib with the point (a, b) in IR2. With this identification, its

absolute value corresponds to the (Euclidean) distance of the corresponding

point from the origin.

The sum of two complex numbers corresponds to the vector

sum of their corresponding points. The

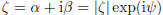

product of two complex numbers is most easily visualized in terms of the polar

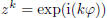

form

with r ≥ 0, hence r = l z l its modulus, and  ∈ IR is called its

argument. Indeed,

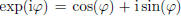

for any real

∈ IR is called its

argument. Indeed,

for any real  ,

,

has absolute value 1, and

has absolute value 1, and

is the angle (in

radians) that the vector

is the angle (in

radians) that the vector

(a, b) makes with the positive real axis. Note that, for z ≠ 0, the argument,

,

is only defined up to

,

is only defined up to

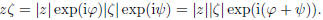

a multiple of 2π , while, for z = 0, the argument is arbitrary. If now also

,

,

then, by the law of exponents,

Thus, as already noted, the absolute value of the product is the product of the

absolute values of

the factors, while the argument of a product is the sum of the arguments of the

factors.

For example, in as much as the argument of  is the negative of the argument of

z, the argument

is the negative of the argument of

z, the argument

of the product  is necessarily 0. As another example, if z = a + ib is of

modulus 1, then z lies

is necessarily 0. As another example, if z = a + ib is of

modulus 1, then z lies

on the unit circle in the complex plane, and so does any power zk of

z. In fact, then

for some real number  , and therefore

, and therefore

. Hence, the sequence

. Hence, the sequence

, appears

, appears

as a sequence of points on the unit circle, equally spaced around that circle,

never accumulating

anywhere unless  = 0, i.e., unless z = 1.

= 0, i.e., unless z = 1.

(17.1) Lemma: Let z be a complex number of

modulus 1. Then the sequence  of powers of z lies on the unit circle, but fails to converge except when z = 1. |

Convergence of a scalar sequence

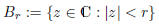

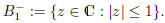

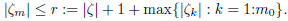

A subset Z of C is said to be bounded if it lies in some ball

of ( finite) radius r. Equivalently, Z is bounded if, for some r,

![]() < r for all

< r for all

![]() ∈ Z. In either case,

∈ Z. In either case,

the number r is called a bound for Z.

In particular, we say that the scalar sequence  is

bounded if the set

is

bounded if the set

is bounded. For example, the sequence (1, 2, 3, ...) is not bounded.

(17.2) Lemma: The sequence

is

bounded if and only if is

bounded if and only if  . Here, . Here,

denotes the kth power of the scalar z. |

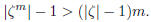

Poof: Assume that

![]() > 1. I claim that, for all m,

> 1. I claim that, for all m,

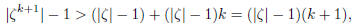

(17.3)

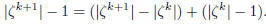

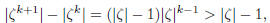

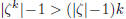

This is certainly true for m = 1. Assume it correct for m = k. Then

The first term on the right-hand side gives

since ![]() > 1, while, for

the second term,

> 1, while, for

the second term,  by induction

hypothesis. Consequently,

by induction

hypothesis. Consequently,

showing that (17.3) also holds for m = k + 1.

In particular, for any given c, choosing m to be any natural number bigger than

,

,

we have  . We conclude that the sequence

. We conclude that the sequence

is unbounded when

is unbounded when

![]() > 1.

> 1.

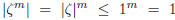

Assume that  . Then, for any m,

. Then, for any m,

, hence the sequence

, hence the sequence

is not only bounded, it lies entirely in the

unit disk

is not only bounded, it lies entirely in the

unit disk

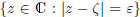

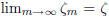

A sequence  of (real or complex) scalars is said to

converge to the

scalar

of (real or complex) scalars is said to

converge to the

scalar ![]() , in

, in

symbols:

if, for all ε > 0, there is some  so

that, for all

so

that, for all  .

.

Assuming without loss the scalars to be complex, we can profitably visualize this

definition as

saying the following: Whatever small circle  of radius ε we

draw around the

of radius ε we

draw around the

point ![]() , all the terms of the sequence except the

first few are inside that circle.

, all the terms of the sequence except the

first few are inside that circle.

| (17.4) Lemma: A convergent sequence is bounded. |

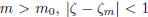

Proof: If  , then

there is some

, then

there is some  so that, for all

so that, for all

.

.

Therefore, for all m,

Note that r is indeed a well-defined nonnegative number, since a finite set of real

numbers always

has a largest element.

| (17.5) Lemma: The sequence

else  , while in the latter case , while in the latter case

. . |

Proof: Since the sequence is not even bounded when

> 1, it cannot be convergent in

> 1, it cannot be convergent in

that case. We already noted that it cannot be convergent when

= 1 unless

= 1 unless

![]() =

1, and in that

=

1, and in that

case  for all m, hence also

for all m, hence also

.

.

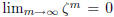

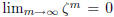

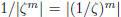

This leaves the case  < 1. Then either

< 1. Then either

= 0, in which case

= 0, in which case

= 0 for all

m, hence also

= 0 for all

m, hence also

. Else, 0 <

. Else, 0 <

< 1, therefore

< 1, therefore

is a well-defined complex number of

modulus

is a well-defined complex number of

modulus

greater than one, hence, as we showed earlier,

grows

monotonely to infinity as

grows

monotonely to infinity as

m→∞. But this says that  decreases monotonely to 0. In other words,

decreases monotonely to 0. In other words,

.

.

Horner, or: How to divide a polynomial by a linear factor

Recall that, given the polynomial p and one of its roots, μ, the polynomial

can

can

be constructed by synthetic division. This process is also known as nested

multiplication or

Horner's scheme as it is used, more generally, to evaluate a polynomial efficiently. Here are the

details, for a polynomial of degree ≤ 3.

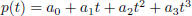

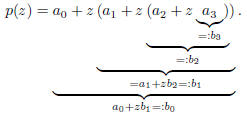

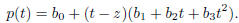

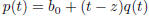

If  , and z is any scalar, then

, and z is any scalar, then

In other words, we write such a polynomial in nested form

and then evaluate from the inside out.

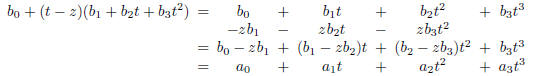

Each step is of the form

"horner (17.6)

it involves one multiplication and one addition. The last number calculated is

, it is the value

, it is the value

of p at z. There are 3 such steps for our cubic polynomial (the definition

requires no

requires no

calculation!). So, for a polynomial of degree n, we would use n multiplications

and n additions.

Now, not only is  of interest, since it equals p(z), the other

of interest, since it equals p(z), the other

are also

useful since

are also

useful since

We verify this by multiplying out and rearranging terms according to powers of

t. This gives

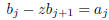

The last equality holds since, by (17.6),

for j < 3 while  by definition.

by definition.

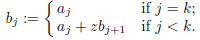

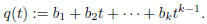

(17.7) Nested Multiplication (aka Horner): To

evaluate the polynomial   at the point z, compute the sequence at the point z, compute the sequence

by the prescription

by the prescription

Then q(t) = p(t)/(t − z). |

Since p(t) = (t − z)q(t), it follows that degq < deg p.

This provides another proof (see (3.21))

for the easy part of the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra, namely that a

polynomial of degree k

has at most k roots.

, with

, with

= 0), then

= 0), then